Defining if Calf Raises are Compound or Isolation: Essential Biomechanics for Serious Lifters

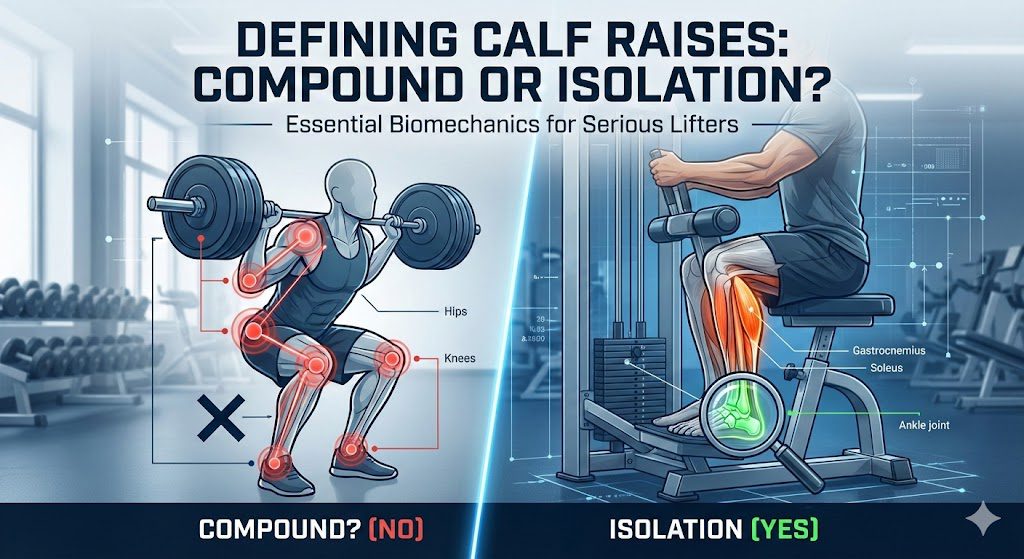

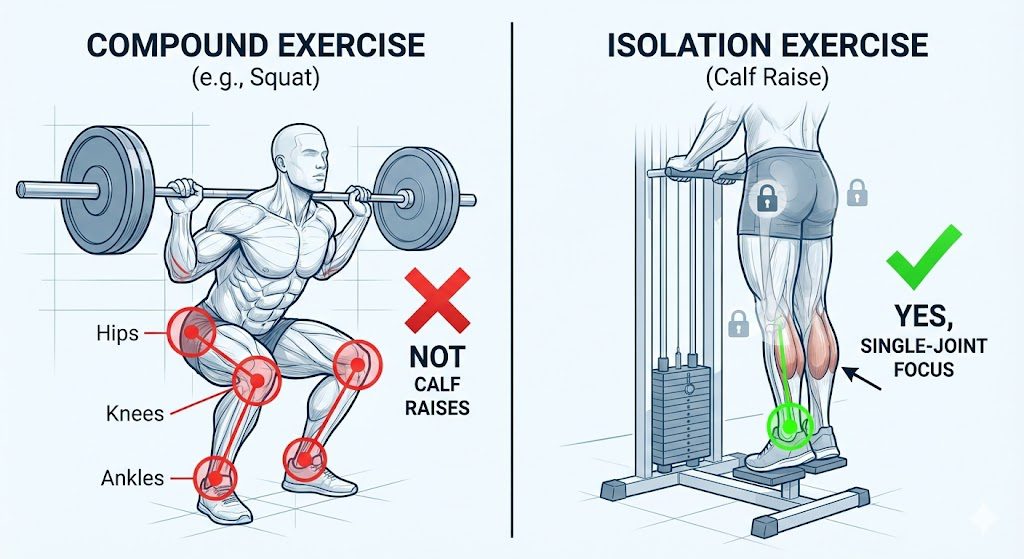

Calf raises are definitively classified as an isolation exercise because they involve movement at only one specific joint—the ankle—and primarily target the triceps surae muscle group without significant assistance from the hips or knees. Consequently, this single-joint mechanic distinguishes them from compound movements like squats, making them the gold standard for targeted lower leg development. Specifically, by locking the knee and hips in place, the load is directed entirely onto the calf muscles, creating a focused stimulus for hypertrophy.

To understand the biomechanics of a calf raise, one must analyze the principle of ankle plantarflexion, where the toes push down against resistance while the body remains stabilized. In this mechanism, the exclusion of multi-joint engagement allows for maximum tension on the target area, eliminating the momentum often generated by larger muscle groups. Furthermore, this strict mechanical isolation is why calf raises remain a staple in both bodybuilding and rehabilitation protocols.

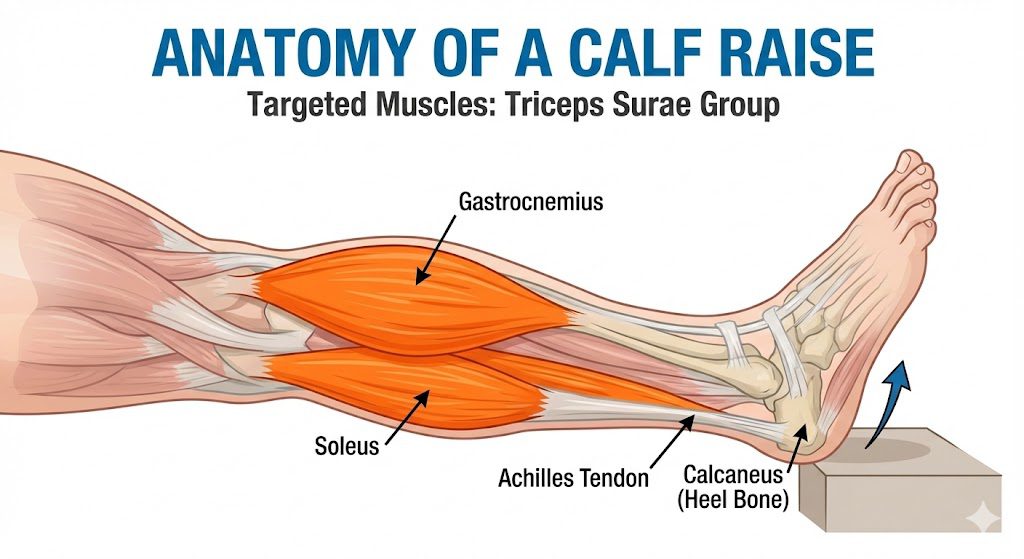

The primary muscles targeted during calf raises are the Gastrocnemius and the Soleus, which together form the powerful calf complex known as the triceps surae. While the Gastrocnemius creates the visible “diamond” shape of the upper calf, the Soleus lies underneath, providing width and thickness to the lower leg. Moreover, understanding the distinct activation patterns of these two muscles is crucial for complete leg development.

However, knowing the classification is just the beginning; you must also master how variations and mechanics affect calf hypertrophy to overcome genetic plateaus. Detailed below, we will explore advanced strategies, including the impact of knee positioning, the myth of compound lifts for calf growth, and the often-neglected tibialis anterior. Let’s explore the essential biomechanics that will transform your leg training.

Are Calf Raises Considered a Compound or Isolation Exercise?

No, calf raises are not a compound movement; they are an isolation exercise because they strictly involve motion at a single joint (the ankle), target a specific muscle group (the calves), and do not require multi-joint coordination.

To clarify, in the realm of resistance training, the distinction is binary based on joint involvement. Unlike a squat or deadlift which recruits the hips, knees, and ankles simultaneously to move a load, a calf raise requires the rest of the kinetic chain to remain static. Consequently, this isolation allows for a direct connection to the muscle without the central nervous system fatigue associated with heavy compound lifts. Specifically, when you perform a calf raise, the load is not distributed across the quads or glutes; it is focused entirely on the plantar flexors.

Furthermore, classifying calf raises as isolation is essential for programming because it dictates volume and recovery. Since isolation movements generally induce less systemic fatigue, they can be trained with higher frequencies and volumes than compound movements. Therefore, recognizing this classification allows lifters to place calf raises strategically within a split to maximize hypertrophy without compromising recovery for larger lifts.

“According to the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA), isolation exercises are defined as single-joint movements that recruit a specific muscle group, making the calf raise a textbook example of isolation mechanics.”

What Defines the Biomechanics of a Calf Raise?

The biomechanics of a calf raise are defined as a single-joint lever system centered around ankle plantarflexion, operating primarily as a second-class lever where the load is positioned between the fulcrum (toes) and the effort (calf muscles).

Specifically, the movement mechanics rely on the stability of the knee and hip to force the ankle joint to do all the work. In this context, the “fulcrum” is the ball of the foot, the “load” is the body weight or external weight, and the “effort” is applied by the insertion of the Achilles tendon on the calcaneus (heel bone). Moreover, this mechanical advantage is what allows the human body to lift heavy loads with the calves, but it also requires a full range of motion to be effective.

How Does Ankle Plantarflexion Create Isolation?

Ankle plantarflexion creates isolation by restricting movement solely to the tibio-talar joint, effectively disengaging the kinetic chain above the knee.

To illustrate, when you press the ball of your foot down (plantarflexion), the calf muscles shorten, pulling the heel upward. During this process, if the knee bends or the hips swing, the isolation is broken, and momentum takes over. Therefore, strict plantarflexion—achieved by keeping the rest of the body rigid—ensures that every ounce of tension is directed into the muscle fibers of the lower leg. Crucially, this bio-mechanical isolation is impossible to replicate with multi-joint movements where the calves act merely as stabilizers.

Which Muscles Are Targeted During Calf Raises?

There are two main muscles targeted during calf raises: the Gastrocnemius and the Soleus, which collectively make up the Triceps Surae group responsible for plantarflexion.

More specifically, while both muscles contribute to lifting the heel, their recruitment levels shift dramatically based on knee positioning. In addition to these, the Plantaris muscle plays a minor, often negligible role. Consequently, a comprehensive calf routine must address the unique architectural differences between the superficial Gastrocnemius and the deep Soleus to build a three-dimensional lower leg.

What Is the Difference Between Gastrocnemius and Soleus Activation?

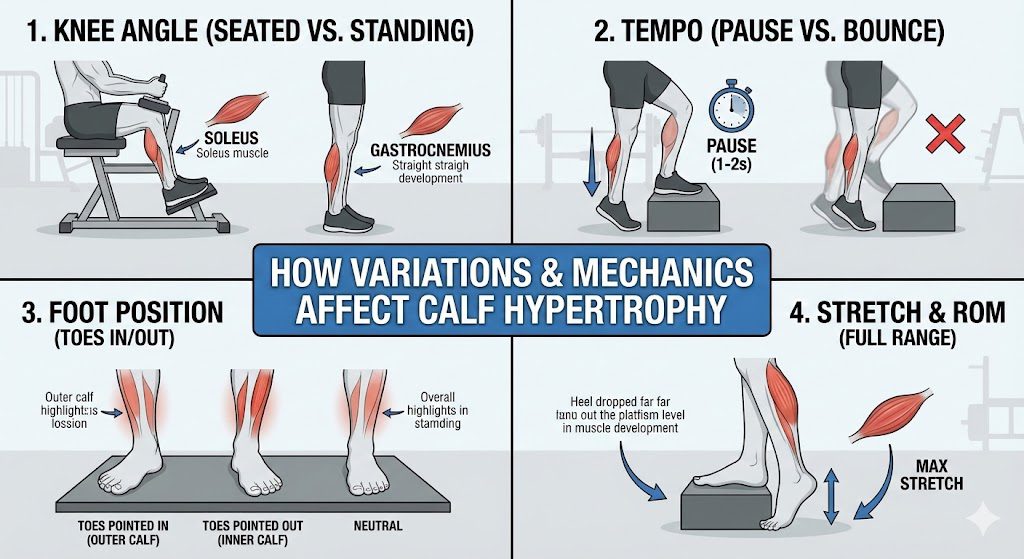

The Gastrocnemius dominates when the knee is straight (extended), whereas the Soleus takes over the workload when the knee is bent (flexed).

Detailed analysis reveals that the Gastrocnemius crosses both the knee and ankle joints (biarticular). Because of this, when the knee is bent, the Gastrocnemius becomes slack (active insufficiency) and cannot produce force effectively, forcing the single-joint Soleus to perform the lift. Conversely, during standing calf raises with straight legs, the Gastrocnemius is stretched and maximally recruited. Thus, to fully develop the calf, a lifter must perform both standing (for Gastrocnemius) and seated (for Soleus) variations.

“Research published in the Journal of Applied Physiology indicates that the Soleus comprises predominantly slow-twitch fibers suitable for endurance, while the Gastrocnemius contains a higher ratio of fast-twitch fibers, responding best to explosive, heavy loads with straight legs.”

When Should You Perform Calf Raises in a Workout Routine?

You should perform calf raises at the end of a leg workout or as part of a specialized accessory session, ensuring they do not pre-exhaust the stabilizers needed for heavy compound lifts.

To explain, the calves play a critical role in stabilizing the knee and ankle during squats, lunges, and deadlifts. If you fatigue them early in the session with high-intensity isolation work, your stability during heavy compounds may be compromised, increasing injury risk and reducing force output on primary lifts. However, for those with severely lagging calves (a priority body part), placing them first is a valid “priority principle” strategy, provided the subsequent compound lifting volume is adjusted.

Generally, the optimal placement is after your heavy quadricep and hamstring work is complete. At this stage, the central nervous system may be fatigued, but because calf raises are an isolation movement requiring less systemic energy, they can still be performed with high intensity. Furthermore, supersetting calf raises with antagonist movements (like tibialis raises) or abdominal work is an efficient way to structure the end of a session.

How Do Variations and Mechanics Affect Calf Hypertrophy?

Variations and mechanics affect calf hypertrophy by altering the muscle fiber recruitment patterns, manipulating the stretch reflex, and changing the length-tension relationship of the muscle complex.

Beyond simple anatomy, optimizing calf growth requires manipulating physics. Specifically, adjusting foot position, knee angle, and tempo can drastically change the stimulus. To navigate this, we must look at how subtle shifts in mechanics—such as the difference between a seated machine and a standing smith machine raise—can mean the difference between stagnation and growth. Let’s examine the specific nuances that separate casual lifting from biomechanical mastery.

Seated vs. Standing: Does Knee Position Alter the Isolation Focus?

Yes, knee position fundamentally alters isolation focus: Standing variations (straight leg) target the Gastrocnemius, while Seated variations (bent knee) isolate the Soleus.

Biomechanically, this phenomenon occurs due to “active insufficiency.” When you sit, the Gastrocnemius is shortened at the knee joint, rendering it mechanically disadvantaged. As a result, the body automatically shifts the load to the Soleus, which only crosses the ankle. Therefore, performing only seated calf raises will result in a wide lower calf but a flat upper calf, lacking that desired “ball” shape. Ideally, a 2:1 ratio of standing to seated exercises is recommended for aesthetic balance.

Can Heavy Compound Lifts Replace Isolation Calf Work?

No, heavy compound lifts cannot replace isolation calf work because during movements like squats, the calves function primarily as isometric stabilizers rather than isotonic prime movers.

While it is true that calves are active during a squat, their length does not change significantly (quasi-isometric) to produce the dynamic contractions needed for maximum hypertrophy. In contrast, isolation calf raises take the muscle through a full stretch and full contraction. Consequently, relying solely on compounds leads to undeveloped calves, as the stimulus is insufficient for significant tissue breakdown and growth. Ultimately, direct isolation work is non-negotiable for maximizing calf size.

Why Is the Tibialis Anterior Often Neglected in Calf Training?

The Tibialis Anterior is often neglected because it is the antagonist to the calf, located on the front of the shin, and is rarely seen as a “vanity muscle,” yet it is crucial for ankle stability and performance.

Functionally, a strong Tibialis Anterior allows for a greater range of motion during calf raises by actively pulling the toes up (dorsiflexion). By training this muscle, you not only prevent common issues like shin splints but also create a thicker appearance to the lower leg when viewed from the front. Moreover, balancing the strong pull of the calves with a strong shin muscle ensures long-term joint health and better force transfer in athletic movements.

Are “Stubborn Calves” a Result of Genetics or Incorrect Isolation Technique?

“Stubborn calves” are often a result of poor isolation technique—specifically lack of a full stretch and pause—rather than just genetics alone.

Although high muscle insertions (high calves) are genetic and cannot be changed, the remaining muscle belly is highly responsive to tension. Unfortunately, many lifters bounce the weight using the Achilles tendon’s elasticity (stretch-shortening cycle) rather than muscular contraction. To correct this, one must pause for 1-2 seconds at the bottom of the rep to dissipate elastic energy, forcing the muscle fibers to move the dead weight. Thus, before blaming genetics, ensure you are performing true, controlled isolation reps.

Co-founder & Chief Marketing Officer (CMO), Optibodyfit

The Architect of Brand Growth Vu Hoang serves as the Co-founder and Chief Marketing Officer of Optibodyfit, creating the strategic bridge between the platform’s technological capabilities and the global fitness community. Partnering with CEO Huy Tran to launch the company in November 2025, Vu has been instrumental in defining Optibodyfit’s market identity and orchestrating its rapid growth trajectory.

Strategic Vision & Execution With a sophisticated background in digital marketing and brand management, Vu creates the narrative that powers Optibodyfit. He understands that in a crowded health-tech market, technology alone is not enough; it requires a voice. Vu is responsible for translating the platform’s massive technical value—an unprecedented library of over 20,000 exercises—into compelling, human-centric stories.

His mandate goes beyond simple user acquisition. Vu leads a comprehensive marketing ecosystem that encompasses content strategy, community engagement, and digital performance optimization. He focuses on solving a core user problem: “decision fatigue.” By structuring marketing campaigns that guide users through the vast database, he helps transform an overwhelming amount of information into personalized, actionable fitness solutions.

Building a Global Community At the heart of Vu’s philosophy is the belief that fitness is a universal language. Under his leadership, the marketing division focuses on cultivating a vibrant, inclusive community where users feel supported rather than intimidated. He leverages data analytics to understand user behavior, ensuring that Optibodyfit delivers the right content to the right person at the right time—whether they are a beginner looking for home workouts or an athlete seeking advanced technical drills.

Commitment to Impact Vu Hoang does not view marketing merely as a tool for sales, but as a vehicle for education and inspiration. His strategic direction ensures that Optibodyfit remains true to its mission of “Elevating Lifestyles.” By consistently aligning the brand’s message with the real-world needs of its users, Vu is driving Optibodyfit to become not just a tool, but an indispensable daily companion for fitness enthusiasts worldwide.